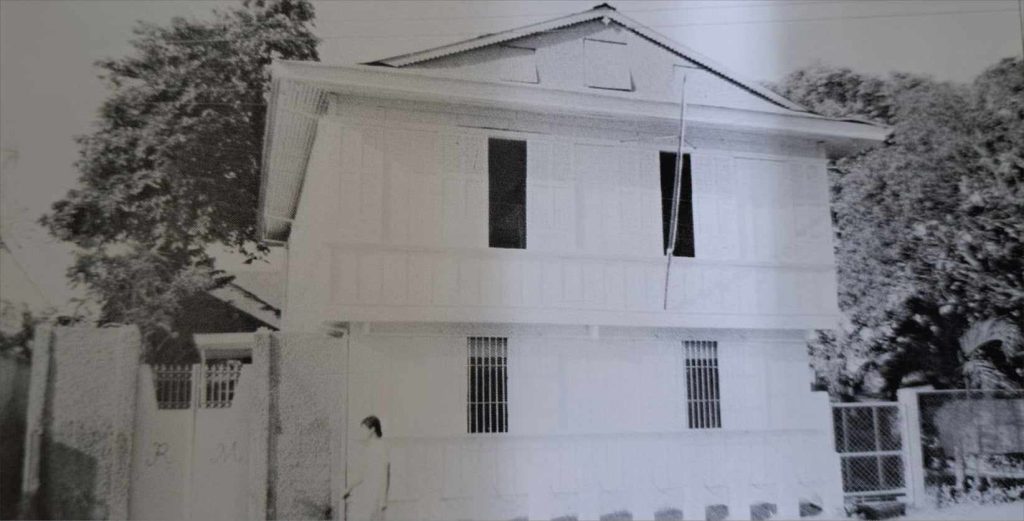

This museum was conceived by the heirs of Don Rosendo Mejica, who was born in Baluarte Molo, Iloilo City, on March 1, 1873. Rosendo Mejica served as councilor of 1loilo from 1906 to 1936. In 1913, he founded and edited Makinaugalingon until 1953. He translated and published the novels of Jose Rizal into Hiligaynon published the translated works of del Pilar and Lopez Jaena, and published the works of several Ilonggo writers like Damaso, Jalandoni, Magahum and Torre. In 1973, during the centennial celebration of Rosendo Mejica’s birth anniversary the National Historical Institute installed a historical marker in the old house at Baluarte as a tribute to the man.

The first step towards the conversion of the old house into a historical shrine was initiated by the U.P. College Iloilo (now known as the Visayas College of Arts and Sciences) through the former dean, Dr. Dionisia A. Rola convinced the Mejica heirs to have the valuable collections organized and later microfilmed. In 1978, there was a formal turnover of the Mejica collection to the college. In 1982, Dr. Rola further recommend to the National Historical Insititute that the old house, where the valuable Mejica collection is housed and preserved by Don Rosendo’s heirs, be converted into a National Historical Shrine. The family agreed to donate the house and lot and everything inside to the national government. The deed of donation was executed on June 16, 1984, and plans for the renovation of the shrine were prepared. The implementation took many years until it was blessed on March 1, 1990, and formally opened to the public on May 1, 1990.

Collections

Collections

The collection of Rosendo M. Mejica covers the period from 1873 to 1978, the bulk of which spans the years from 1913 to 1941. It consists primarily of copies of the Makinaugalingon newspaper, imprints of the Makinaugalingon Printing Press, bibliographical features, memorabilia, albums, memorials, scrapbooks, photographs, greeting cards, invitations, and programs, family records, and other printed materials.

The collection reflects the political, social, cultural, economic, and intellectual growth of Iloilo. Reading the Makinaugalingon issues is like seeing Iloilo in its yesteryears. The objectives of the Makinaugalingon, the editorials, the published speeches, and the literary productions of prominent Ilonggo writers of the time provide insights into the temperament and aspirations of the Illonggos during Mejica’s time. Some biographical sketches of Mejica written by his friends and children are reflective of the episodes occurring from 1873 to 1956.

The Makinaugalingon imprints are valuable materials for research on local history, vernacular literature, and socio-economic problems.

Mejica’s Filipiniana collection consisting of more than 200 titles, some of which were published early as 1865, is a source of data for Philippine studies.